Ephemeral Bloom: The Fading Romance of Bias-Cut Evening Gowns

There’s a particular melancholy that settles over me when I’m surrounded by antique sewing patterns. Not a sadness of loss, precisely, but a quiet reverence for the hands that once drafted them, the dreams they represented, and the fleeting beauty they promised. Among these treasures, the bias-cut evening gowns of the 1930s and 1940s hold a special, almost heartbreaking allure. They are echoes of a glamourous era, a testament to an almost lost craft, and a tangible reminder that even the most exquisite things are subject to the passage of time.

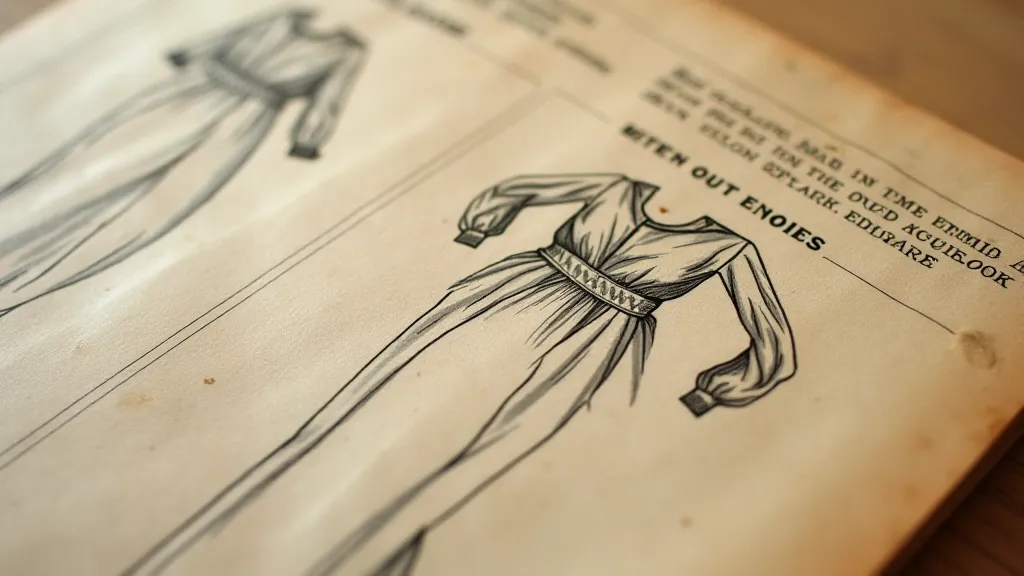

I remember the first time I encountered a bias-cut gown pattern. It wasn’s in a pristine condition; the paper was brittle, the instructions faded, and a corner was delicately torn. But even in its fragility, it whispered stories of satin shimmering under ballroom lights, of whispered secrets and stolen glances. It felt less like a piece of paper and more like a portal to another world.

The Allure of the Bias

What made these gowns so captivating wasn’t merely their aesthetic—though the drape, the flow, the way they clung and swirled was undeniably mesmerizing. The secret lay in the technique: the bias cut. Unlike cutting fabric on the straight grain or cross grain, the bias cut involves cutting at a 45-degree angle to the warp and weft. This seemingly simple adjustment transformed the very nature of the fabric, granting it an unparalleled elasticity and fluidity.

Imagine a bolt of silk charmeuse, rigid and unforgiving when cut straight. Now, imagine that same fabric, draped and molded to the body with a soft, liquid grace. That’s the magic of the bias cut. It allowed designers to create gowns that flowed and moved with the wearer, hugging the curves and accentuating the silhouette in a way that was simply impossible with traditional cutting methods. It wasn’t just about making a dress; it was about creating a work of art, a sculpture in fabric.

A Time of Innovation and Restraint

The rise of the bias cut was intrinsically linked to the social and technological shifts of the 1930s and 1940s. The ‘30s brought a loosening of restrictive Edwardian silhouettes, paving the way for more fluid and form-fitting designs. Simultaneously, advances in fabric production allowed for the widespread availability of luxurious materials like silk charmeuse, rayon crepe, and velvet, all of which were perfectly suited to the bias-cut technique.

The Second World War, however, significantly impacted fashion. Fabric rationing and austerity measures meant that bias cutting, which required significantly more fabric than simpler cutting methods, became less practical. While it didn't disappear entirely, its prevalence waned considerably. The emphasis shifted towards more economical and utilitarian designs. This period represents a crucial turning point – the twilight of a particular kind of elegance.

The Craftsmanship: A Lost Art?

Creating a bias-cut gown was, and remains, a painstaking process. It required an intimate understanding of fabric behavior, meticulous pattern drafting, and exceptional sewing skills. The patterns themselves were often complex, featuring multiple bias-cut pieces that needed to be precisely matched and sewn together. A single gown could take days, even weeks, to complete.

The seamstress – often working in a small atelier – was not merely a maker of clothes, but a skilled artisan, a silent collaborator in the creation of beauty. The subtle variations in hand-stitching, the careful pressing of seams, the tiny details that elevated a garment from "made" to "masterpiece" – these were the hallmarks of a truly exceptional bias-cut gown.

Today, few possess the full spectrum of skills necessary to faithfully recreate these gowns. Pattern drafting, in particular, is a dying art, reliant on intuition and experience rather than computerized precision. The fabric itself, the quality of silk charmeuse of the 1930s and 1940s, is difficult to replicate. Even the needles and thread used at the time held a unique quality contributing to the final look and feel. This scarcity contributes to the allure of restored or original pieces.

Collecting and Restoration: Preserving a Legacy

For those captivated by the romance of bias-cut gowns, collecting or restoring them offers a unique opportunity to connect with the past. Original gowns, particularly those in excellent condition, are highly prized and can command significant prices. However, many more are available as patterns, allowing enthusiasts to experience the construction process firsthand.

Restoration, however, is a delicate process. Damaged fabric is often irreparable, but careful cleaning and mending can preserve the integrity of the garment. Understanding the construction techniques is crucial; simply patching a tear can compromise the drape and flow of the gown. Seeking advice from experienced textile conservators is highly recommended. The goal isn't to make the gown "new," but to stabilize it and prevent further deterioration, allowing its story to endure.

Even working with the patterns themselves can be restorative. The meticulous drafting, the precise instructions (even those faded and challenging to decipher), the opportunity to understand the steps involved in creating something so elegant - it fosters a respect for the craft that's so often lost in our fast-paced world.

The Enduring Allure

The bias-cut evening gown represents more than just a garment; it embodies an era of elegance, craftsmanship, and innovation. Its fleeting popularity serves as a poignant reminder of the cyclical nature of fashion and the ephemeral beauty of all things. While the heyday of the bias-cut gown may be over, its allure remains, whispering tales of a glamorous past and inspiring contemporary designers to explore the possibilities of fabric and form. Each surviving gown, each pattern carefully preserved, is a small victory against the relentless march of time – a testament to the enduring power of beauty and the human desire to create something truly exquisite.