The Geometry of Grace: Deconstructing the Dior ‘New Look’ Silhouette

There’s a certain magic that clings to vintage sewing patterns. It’s more than just nostalgia; it’s a tangible connection to a time when craftsmanship and elegance were prized above all else. Holding a fragile, yellowed pattern from the 1940s or 1950s is like holding a secret, a whisper from a bygone era. And few silhouettes are as iconic, as immediately recognizable, and as intrinsically linked to that era as the Dior ‘New Look’.

I remember the first time I encountered a pattern for a ‘New Look’ dress. I was sifting through a box of my grandmother’s old belongings, a treasure trove of faded photographs and forgotten memories. Nestled amongst the lace doilies and moth-eaten scarves was this pattern, meticulously folded and labeled with a date from 1951. It wasn't just the pattern itself that captivated me, but the promise it held – the potential to recreate a moment in fashion history, to understand the artistry behind a style that continues to inspire.

Christian Dior’s post-war collection, presented in 1947, was a seismic event in the fashion world. Emerging from the austerity of wartime rationing, the ‘New Look’ was a defiant embrace of femininity, a celebration of curves and luxurious fabrics. It was a direct response to the utilitarian, boxy shapes that had dominated fashion during the 1940s. But to simply call it beautiful doesn't quite do it justice. The genius of Dior wasn't just in his aesthetic choices, but in his understanding of the underlying mathematical and architectural principles that underpinned the silhouette.

The Architecture of the Silhouette

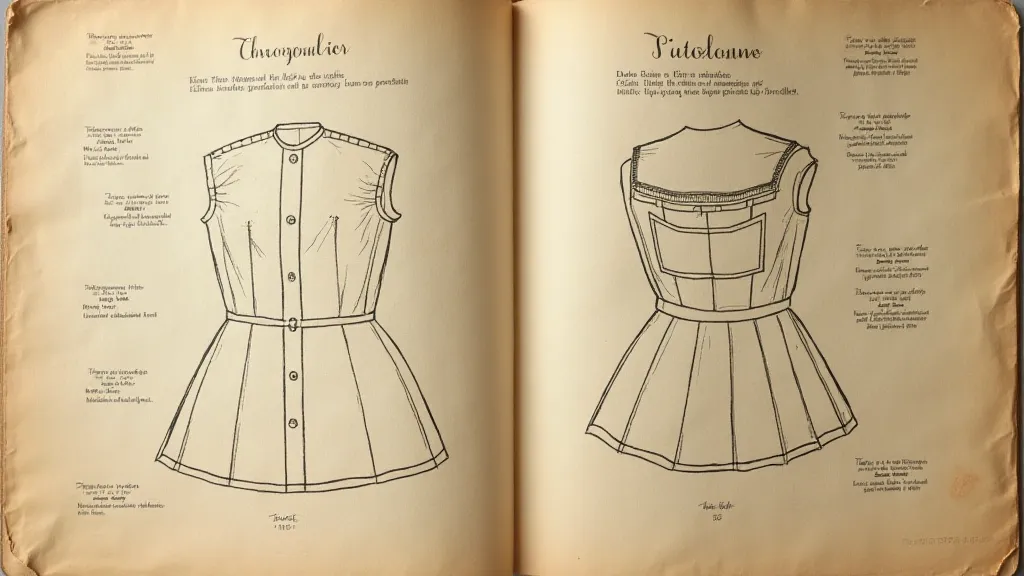

Look closely at a ‘New Look’ pattern – or even a photograph of a dress from the collection – and you’ll begin to see the structure. The defining features – the nipped-in waist, the full, A-line skirt, the rounded shoulders – weren’t simply decorative elements. They were carefully calculated to create a specific visual effect, a perception of harmony and balance. The waist, dramatically reduced to approximately 18 inches (compared to the looser, straighter waists of the 1940s), created a strong visual contrast with the voluminous skirt. This wasn't accidental; it was deliberate. The silhouette was designed to draw the eye, to emphasize the hourglass figure.

The skirt itself, often reaching just below the calf, was constructed with layers upon layers of fabric – often yards and yards of luxurious wool or silk. The fullness wasn't simply achieved through gathering; it was carefully engineered. The pattern pieces were strategically cut and sewn to create a controlled volume, preventing the skirt from appearing shapeless or overwhelming. Consider the pleating and the precisely placed gathers—each element served a purpose in maintaining the skirt's distinctive flare.

Mathematical Harmony & the Golden Ratio

Beyond the obvious visual impact, there’s evidence to suggest Dior and his design team were aware of, and potentially employed, principles of mathematical proportion. The application of the Golden Ratio – approximately 1.618 – can be observed in the relationships between different parts of the silhouette. The ratio appears in the proportions of the bodice, the length of the skirt, and the overall balance of the dress. While it's difficult to definitively prove Dior consciously applied the Golden Ratio, its presence is suggestive of a deeper understanding of aesthetic harmony. The visual effect it creates is undeniably pleasing to the eye, and its deliberate application, if present, would have added a layer of sophistication to the design.

The rounded shoulders, too, contribute to the overall sense of softness and femininity. They create a gentle curve that softens the lines of the bodice and complements the fullness of the skirt. The neckline, often a boatneck or a soft scoop, further emphasizes the graceful curve of the shoulders and décolletage. The entire ensemble works together to create a harmonious whole – a testament to Dior’s masterful understanding of proportion and balance.

Craftsmanship & Materials

Of course, even the most perfectly designed pattern requires exceptional craftsmanship to bring it to life. The ‘New Look’ was as much about the quality of the materials as it was about the design itself. Dior favored luxurious fabrics – wools, silks, taffetas, and organzas – that draped beautifully and held their shape. The construction techniques were equally important. Seams were meticulously finished, linings were flawlessly applied, and every detail was carefully considered. The emphasis was on quality and durability – a reflection of a time when clothing was meant to last.

Finding vintage 'New Look' patterns can be a rewarding pursuit for any sewing enthusiast. They’re often fragile and require careful handling, but the opportunity to recreate these iconic designs is truly special. Many patterns are available online, often in downloadable PDF format, making them accessible to sewers of all skill levels. Even if you're a beginner, don't be intimidated – start with a simpler variation of the 'New Look' silhouette and gradually work your way up to more complex designs.

Restoration & Collecting Considerations

For those interested in collecting vintage sewing patterns, preservation is key. Patterns should be stored flat in acid-free folders or tissue paper to prevent damage from moisture and sunlight. Handling patterns with clean hands is also crucial, as oils from your skin can degrade the paper over time. Small tears or holes can often be repaired using archival-quality paper and adhesive.

When restoring patterns, it's important to use the gentlest methods possible. Avoid harsh chemicals or excessive heat, as these can damage the paper and fade the ink. If you're unsure about a particular restoration technique, it’s always best to consult with a professional paper conservator.

The allure of the 'New Look' extends far beyond mere fashion. It’s a symbol of resilience, optimism, and a return to grace after a period of hardship. By studying its design principles and recreating its iconic silhouettes, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the artistry and craftsmanship of a bygone era – and perhaps, even find inspiration for our own creative endeavors.